Progress

- Pre-assessment (Completed)

- Project Design (Completed)

- Project Started (Completed)

- Project Finished (Completed)

- Monitoring Active (In Progress)

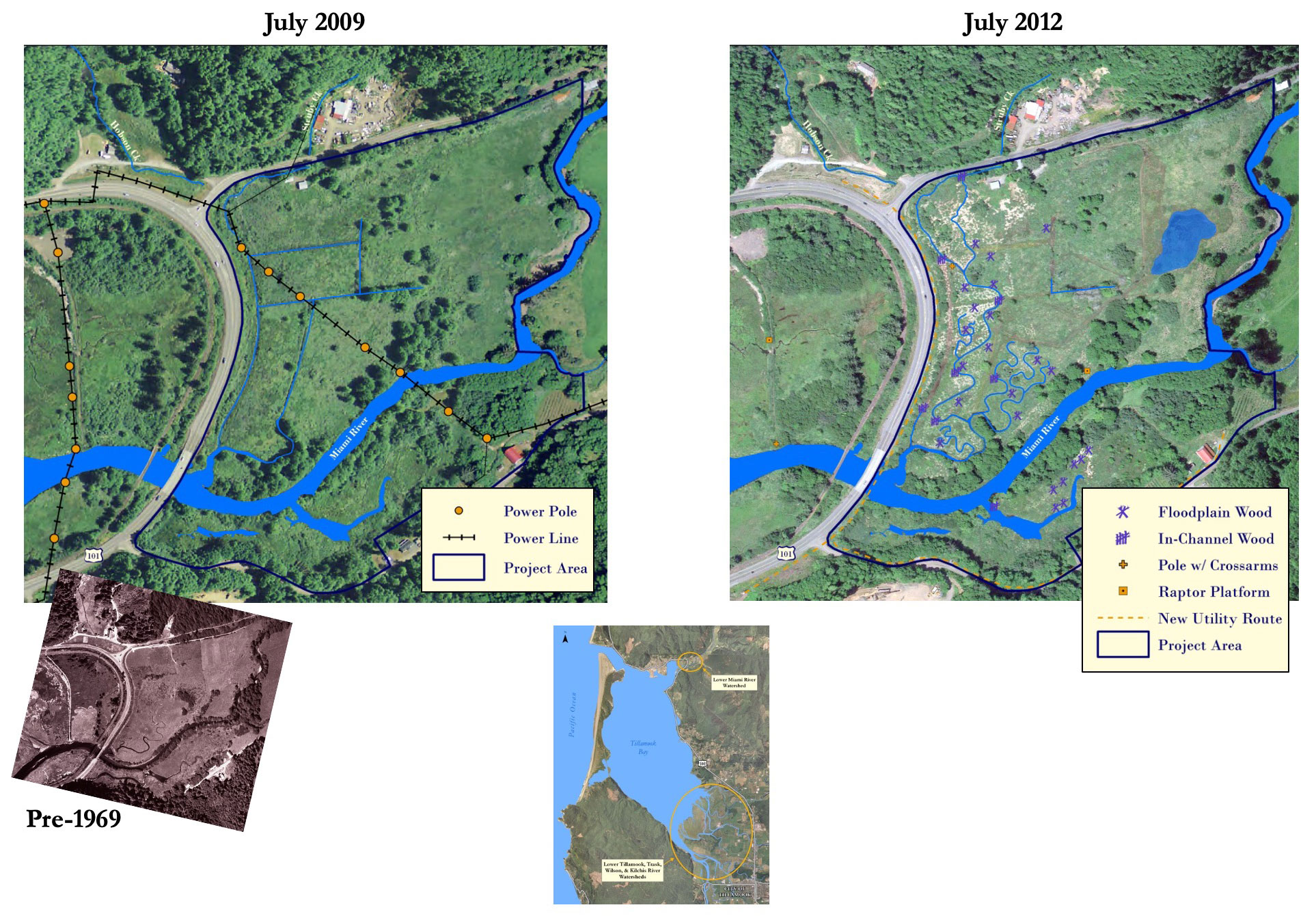

Diking, draining, and other human activities have adversely affected much of Tillamook County’s wetlands. An estimated 85% of Tillamook Bay salt marsh wetlands have been altered. In 2004, TEP was privileged to be approached by a private landowner to lead the charge of restoring wetlands on their property in the lower Miami Watershed. Together with twenty federal, state, and local partners, TEP restored the ecologically important tidal spruce swamp where fresh water from the Miami River meets salty water from Tillamook Bay. This type of habitat is vital for juvenile salmon as they transition from fresh water to salt water.

Even in the Land of Many Waters, the Miami River is unique. While four of the five rivers flowing into the Tillamook Bay are clustered relatively close together at the southern end of the bay, the mouth of the Miami opens into the northern end, tucked just below the Port of Garibaldi. Historically, the Miami wetlands hosted a tidal spruce swamp, now a rarity along the Oregon and Washington coastline. Tidal spruce forests create shady, secure habitat for a variety of salmonids, including Chinook and Chum Salmon. Although Tillamook Bay stretches the southern end of the Chum Salmon range, the Miami is one of the three watersheds within the bay that supports the largest Chum population on the Oregon Coast. Juvenile Chum behave differently than other salmon species, leaving their hatching ground early and relying heavily on healthy estuarine wetlands for critical habitat, underscoring the relevance of the restoration and improvement of the Miami Wetlands Project.

The Miami Wetlands Restoration has also been good for the local economy. Over $1.8 million was invested in the project from a variety of sources: local, state and federal agencies, nonprofits, public and private utilities, and private landowners. Thirty family-wage jobs were supported directly through the restoration — engineers, scientists, construction workers, excavation contractors, planting and maintenance crews; all hired locally whenever possible. Project expenses, including permits, construction supplies and equipment rentals, also directed money into local entities. Additionally, good habitat restoration is the gift that keeps on giving; as habitat improves, fish stocks improve, so does catch for commercial and sport fisheries. In the web of life of rural economies, good fishing is a building block of the commercial industry and a foundational piece of coastal tourism.

Often, restoration projects are agency driven, with partnerships developed out of necessity for access or funding. The Miami Wetlands was unique from the outset — a private landowner initiated the project, approaching Tillamook Estuaries Partnership and engaging his neighbors to literally provide the base for the project. As the potential for the site unfurled, agencies, utilities, and conservation partners all climbed on board, working together to accomplish one of the premier restoration projects on the Oregon Coast.

Project Details

Reports & Publications

-

Miami Wetlands Enhancement Project: Six-Year Post-Implementation Monitoring Report - Part 1

-

Miami Wetlands Enhancement Project: Six-Year Post-Implementation Monitoring Report - Part 2

-

Miami Wetlands Enhancement Project: Six-Year Post-Implementation Monitoring Report - Part 3

-

Miami Wetlands Enhancement Project: Six-Year Post-Implementation Monitoring Report - Part 4

-

Miami Wetlands Enhancement Project: Six-Year Post-Implementation Monitoring Report - Part 5